Es gibt noch mehr Kirchen zu sehen, als ich davon sprach, nach Trier zu reisen, erwähnte mein Vater die Konstantinbasilika. Und schon stehe ich davor, nachdem ich an einem wuchtigen, quadratischen barocken Turm vorbei gekommen bin, der sich später als Glockenturm der Basilika erweist.

Aber es ist geschlossen, der liebe Gott macht Mittagspause bis 14 Uhr und ich befolge dieses göttliche Gebot und suche nach einem Café. An die Kirche angebaut ist das Kurfürstliche Palais, einst der Sitz der Herrscher der Stadt, die Bischöfe und Kurfürsten in Personalunion waren, und wenn man öffentlich Wasser predigt und zu Hause Wein trinkt, dann muss man das in passendem Ambiente tun. An das Palais schließt sich der Palastgarten an, eine schöne kleine Parkanlage mit Teich in der Mitte, herbstlichen Blumenrabatten und den barocken Figuren von Ferdinand Tietz, die ich auch schon im Stadtmuseum gesehen habe. Und hier finde ich auch ein kleines Café, es gibt Kartoffelsuppe, Moselwein und einen Blick auf See und Enten.

Zurück zur Konstantinbasilika. Spoiler-Alarm, es ist gar keine Basilika, weder von der Architektur, denn es ist keine dreischiffige Kirche, noch von der religiösen Ausrichtung, die Kirche ist evangelisch. Den Namen Konstantinbasilika fand ein Heimatforscher in alten Schriften und den Leuten hat es scheinbar gefallen und so blieb der Name.

Das Gebäude ist eine Palastaula, ein Empfangssaal, eine Audienzhalle, die zum Palast von Kaiser Konstantin gehörte. Die Geschichte des Hause ist so wechselvoll wie die Geschichte der Stadt, sie war irgendwann eine ausgebrannte Ruine, wurde von den Bischöfen übernommen und zur Trutzburg ausgebaut, später wurde sie in das neu gebaute oben erwähnte Palais integriert, nachdem 1614 Ost- und Südwand entfernt wurden. Ab 1844 wurde das Kirchengebäude wieder hergestellt und 1856 der evangelischen Gemeinde „auf ewige Zeit“ (das ist ganz schön lange) übergeben. Im August 1944 durch einen Luftangriff schwer getroffen, brannte sie völlig aus und wurde in den 50er Jahren restauriert.

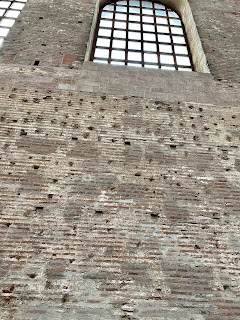

Die Ausstattung ist minimalistisch. Schon von außen hatte ich das Gefühl, vor einem Industriedenkmal zu stehen. Es gibt nur wenige Verputzreste aus der Römerzeit, die in den Fensterlaibungen erhalten sind, sonst sind die Mauern unverputzt und zeigen die römischen Ziegel (Westmauer) mit den Öffnungen, die zum antiken Heizungssystem gehören (Aussenmauer) und den Löchern, in denen einst die Metallhaken befestigt waren, die die Marmorverkleidung trugen (innen).

Beim Wiederaufbau wurde bewusst auf jede Ausmalung und andere Dekoration verzichtet, es gibt eine beeindruckende Holzkassettendecke und einen minimalistisch gestalteten Altarraum und zwei Orgeln. Und weil es hier von allem ganz wenig gibt, fallen die vier klassischen Statuen, genau genommen die Köpfe von klassischen Statuen dann recht schnell ins Auge. In den Jahren 1880 bis 1887 schuf der Frankfurter Kunstprofessor Gustav Kaupert für die Kirche doppelt lebensgroße Statuen von Jesus und den Evangelisten, die in Nischen hinter dem Altar standen. Den Bombenangriff und den Brand überstanden die Figuren fast unbeschadet, die Renovierung in den 50ern nicht. Bei den Renovierungsarbeiten fand man sie zerstört am Boden liegend, Bilderstürmerei als Zeitgeist gewissermaßen. Das Presbyterium beschloss, die Köpfe aufzubewahren, der Rest wäre zwar Kunst, könne aber trotzdem weg. Die Kirche sollte eben wieder ursprünglich aussehen, wie zur Römerzeit. Ein interessantes Oxymoron, denn das hätte doch bedeutet, das Gebäude von der evangelischen Gemeinde zu befreien und es in eine römische Aula zu verwandeln. Oder? Die Köpfe wurden 2001 restauriert und werden nun in der Kirche ausgestellt. Ein Tupfen Klassizismus in den Industrie-Interieur.

English version below

There are more churches to be seen, when I talked about going to Trier my father mentioned the Konstantinbasilika (Aula Palatina). And I’m already there, after passing a huge quadratic baroque tower, which turned out to be the bell tower of the church.

But it is closed, the Lord is at lunch break and I follow this commandment and search for a cafe. Attached to the church is the Electoral Palace, once the seat of the rulers of the city who were bishops and electors in one person and when you preach in public to drink water and take the wine at home in secret you need the fitting surroundings. To the palace belongs the palace garden, a neat little park with a pond and autumn like flower beds and the baroque statues, I already saw at the city museum. And I find a little cafe too and had potatoes soup, Mosel wine and a lovely view onto the pond with the ducks.

Back at the Konstantinbasilika. Spoiler alert, it’s neither a basilica, since it’s not a three-nave church, nor it’s a basilica religion-wise, since it’s not catholic. The name was found by a local history researcher in an old report in the end of the 19th century and people seem to like it, so it sticks.

The building is an Aula Palatina, a meeting hall, a grand reception room, that belongs to the palace of emperor Konstantin. The history of this place is a chequered as the history of the city. It came into the possession of the bishops as a burnt ruin, was turned into a fortress, became part of the electoral palace after the east and southern walls were removed, was rebuilt as a church in the middle of the 19th century and given to the Protestant church for ‘eternal time’ (wow, that’s a really long time). In August 1944 it was hit during an air strike and burned down and was rebuilt and restored in the 50s.

The features are minimalistic. Even from the outside, I got the impression of an industrial memorial. There are very few render leftovers from the Roman era in the window flannings, all the walls are without any grouts and show the Roman tiles (west walls), the vents that belong to the antique heating system (outside wall) and the holes for metal hooks that once hold the marble plaster (inside walls).

At the reconstruction they purposely renounce any murals or ornaments, there is a very impressive wooden waffle-slap ceiling, a minimalist altar and two organs. And because there is so few of everything you instantly be aware of four classical statues, or, to be precise the heads of four statues. In the years 1880 to 1887 the Frankfurt based Art Professor Gustav Kaupert made those double life-sized figures of Jesus and the evangelists for the church and they were displayed in niches behind the altar. The bombing and burned they survived nearly unscathed, but the reconstruction in the 50s not. They have been found laying in the ground, smashed, iconoclasm as zeitgeist and the presbytery decided to keep the heads and anything else was declared rubbish. The church must look original, like at Roman time, what is a bit an oxymoron, since there was no Lutheran church at this time, that means remove the Protestant church from the building and make it an emperor’s reception hall again. Right? The heads have been renovated in 2001 and are displayed Noor in the church. A blob classicism in an industrial interior.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen